Constraints Force Creativity

Considering the Work of Poet Philip Larkin

“The widest prairies have electric fences” (Larkin 57, Line1)

I was introduced to Larkin’s writing as a desultory 19 year old community college student. I drove a 1991 Toyota Celica that smelled of spilt turpentine and had a small trunk full of charcoal newsprint drawings. At the time, I was checking off boxes on a college transfer guide and needed a second English course. The process of selecting a class schedule seemed arbitrary and I chose this particular literature class because it mentioned the word “poetry” in the course description. Learning about poems seemed more interesting than whatever the alternative was.

I remember purchasing the assigned book of Larkin’s Collected Poems from the student store for a discounted used book price. I flipped through the pages and landed on “wires” which opened “The widest prairies have electric fences”. This beautiful sentence changed me. It remains my favorite opening line in poetry to this day. The rest of the poem reads:

For though old cattle know they must not stray Young steers are always scenting purer water Not here but anywhere. Beyond the wires Leads them to blunder up against the wires Whose muscle-shredding violence gives no quarter. Young steers become old cattle from that day, Electric limits to their widest senses.

I don’t know exactly what it was about the work that shocked me into paying attention to it, but I found myself staying up late analyzing sentences, thinking about phrasing and writing 10 page long essays for two-stanza poems. It was bleak but humorous, profound and cynical all at once, and it was endlessly challenging.

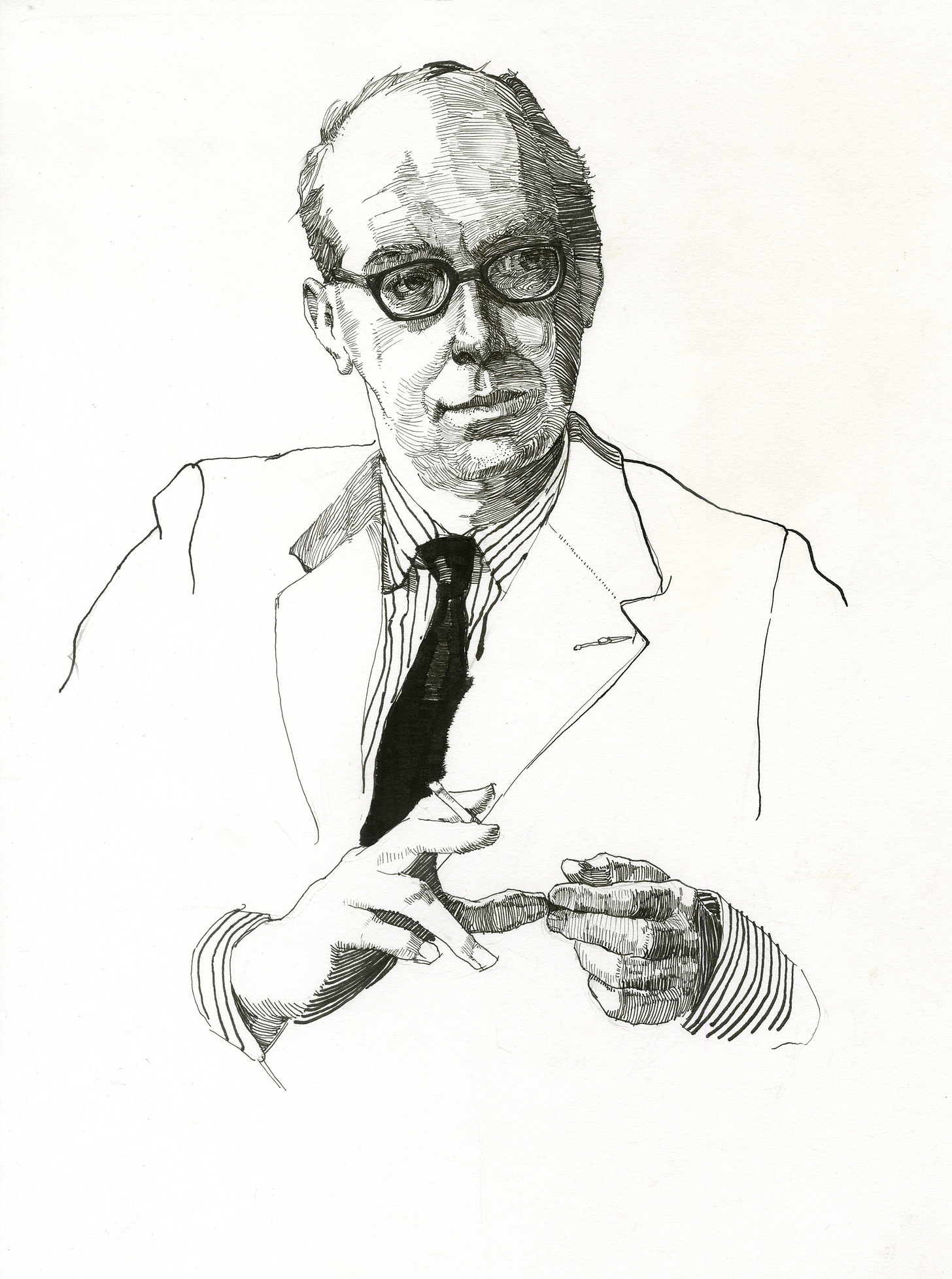

*(Yes, I spilled paint on it at some point, I’m surprised it looks as intact as it does after 15 years in the studio.)

I revisit these pages often. One of the things that stood out to me when I first read Larkin’s works was the fact that most poems followed a rigid and often complex rhyme structure. This seemed a remnant of an older time and in fact, Larkin consciously rebuked the more modernist free-verse writing that was fashionable at the time. Larkin belonged to a writing collective called The Movement which was a literary movement in England in the 1950’s. The Movement opposed American Modernist writing and opted instead for traditional poetic devices and creating work from personal experience. Larkin believed that the personal was a more powerful source for art than referencing history or literature. In spite of keeping with stringent rhyme schemes and meter, Larkin’s poems often feel conversational and personal. His technical mastery in blending these traditional formal poetic structures with the conversational is often praised.

Having a defined structure, or set of limits, when approaching a large idea feels counterintuitive. It would seem that one would need endless ways of saying something in order to properly say the thing in the best way. Wouldn’t a restrictive formula only stifle creative output? This isn’t the case and in fact, some of the most powerful poems keep to a structure, the same is true for paintings. Francis Bacon stated in an interview with David Sylvester “I want a very ordered image, but I want it to come about by chance”. In this interview, Bacon explains his difficulty working in a fully abstracted way. Bacon utilized a defined a structure to build abstraction and expression atop. When grounding a work in a structure or set of parameters, there are avenues that are arrived at in a way which can surprise the artist.

Larkin wrote so many great lines that cling to the amygdala and I can’t help but think that some of this is due to the parameters that he set for himself. There are phrases in poetry that come about out of necessity when aiming to solve a formal puzzle. For example, the following is the second and final stanza from “Home is So Sad”:

And turn again to what it started as, A joyous shot at how things ought to be, Long fallen wide. You can see how it was: Look at the pictures and the cutlery. The music in the piano stool. That vase.

Following an ABABA structure, this stanza builds out the imagery of the home that has been left to exist without you. The structure that the poem uses necessitates that the ending has the sound of the soft “Vase”. I wonder if Larkin would have chosen a different way to end this poem if he were not confined to complete the rhyme with “was”. It’s such a specific image to end on, “That Vase”. This is made more abrupt by Larkin’s choice to make those two words into an entire sentence, separating the thought and making the ending more stark.

Larkin sometimes chose free verse writing if the idea of the poem called for it, but more often than not, he’d keep to a rhyme scheme. Structure also reinforced the concept. Take the second stanza from “This be the Verse” for example:

Man hands on misery to man. It deepens like a coastal shelf. Get out as early as you can, And don’t have any kids yourself.

The choice to employ a simple ABAB structure here frames the theme of the poem. The idea that “Man hands misery to man” in this dumb cosmic condemnation to proliferate endlessly. The structure here is an almost flippantly simple ABAB, and it seems to aid in the idea that this cycle itself is a simple one to recognize. It’s presumably easy to step outside of; “Don’t have kids yourself”. Having a structure, again echoes the sentiment of the poem as a cyclical pattern of nature.

Philip Larkin was a miserly pessimist who was obsessed with death and sorrow from a young age. But his work also contains profound hope and hints of romanticism. I think one could say that a cynic is one whose deeply romantic nature has soured. One of his most famous lines is the final from “An Arundel Tomb” and reads “what will survive of us is love”.

Background on Larkin

Philip Larkin was born in Coventry. England in 1922. He had poor eyesight and a stutter which led him to retreat into books and writing. He went on to study English at St. John’s College, Oxford where he befriended writer Kingsley Amis and the two became lifelong friends. Larkin worked in libraries his entire life, ultimately ending up in Hull as head librarian. As his popularity grew, he retreated from the limelight and chose to work and write from Hull. He once wrote of Hull “I’m settling down in Hull alright, Every day I sink a little further”.

Larkin structured his life in as rigid a way as he structured his poems. He rejected the conventional human aims of marriage and children and he opted for neither. He kept a job he often bemoaned and chose to live in a gloomy parochial town which he described as “smelling of fish”. He complained about the lot that he chose for himself.

Whether consciously or not, Larkin ordered his existence such that his writing was the most important thing, but one which he did only in the outskirts of his career as a librarian, even despite his success as a writer. He was a contradiction in many ways, just as his poems are contradictory as well.

In one of his most famous poems, Toads, Larkin analogizes the idea of work with that of a metaphorical toad. The poem explores the limiting reality of spending most of one’s waking hours working to earn a living. Toads opens:

“Why should I let the Toad Work/ Squat on my life?” (Larkin 62, line1)

The metaphor of the toad as an ominous force which compresses one’s will and limits one’s life is a powerful idea. Larkin lamented his disdain for work and its seemingly inescapable burden on one’ life, choking out all manner of possibility. Exchanging complete freedom for a regular paycheck and conventional security. When complete freedom is weighed against the investment of one’s time, Larkin laments:

“Just for paying a few bills, that’s out of proportion” (Larkin 62, Line 7)

Larkin acknowledges the constraint of his circumstance as a reflection of his character. This is expressed in line 62 which reads:

“For something sufficiently toad-like/ squats in me too;” (Larkin 62, Lines 25 & 26)

"Something “sufficiently toad-like” is what keeps Larkin in this reality that he protests. The disquiet and resentment that Larkin displays in his writing becomes an integral part of his voice.

“Deprivation is for me is what daffodils were for Wordsworth.”

-Philip Larkin

The limits that Larkin built to contain his life are the electric fences that he describes in Wires. Life offers many external limitations which violently shock young cattle into old cattle, but many limits are self imposed as well. In Larkin’s case, this was where he derived the fuel for his words.

Early on as an art student in college, I felt that an open-ended assignment was very difficult to begin. Despite the common protest among my peers that we were being confined to the bounds of a design 1 final, the day I was given the chance to make my own art and to make it however I wanted, was daunting.

Suddenly, I had to figure out what material I wanted to use, how I wanted to use it and what I wanted to even say in doing so. The price of freedom then felt like eliminating all possible directions and choosing only one, assuming I could even accomplish it with my freshman skillset. I made a brownish muddled mess of a painting on a flimsy canvas board. I don’t even remember what it looked like, but I remember the mess.

Expressive mark making was something I would return too, but I needed the rigid school structure to get me there. I needed to paint the swatches and make the muddled messes to figure out the set of parameters that I would work within which I could later called a style.

Many artists will say that having limitations in some ways has forced them to become more creative. With parameters, there is an imperative to solve something and to unearth solutions for a piece or to a body of work. Having something to resolve is a motivating force in artmaking. A challenge to overcome is more exhilarating than simply pushing paint endlessly without a deadline or criteria.

As a counterpoint to this idea, I would acknowledge that many of the great art movements of history are in response to a more restrictive age. They are a rebuke of the established salon, or the “ism” that came before. I would argue that the limitations of the prior era are still, in this case, the catalyst for finding new ways of expression, or perhaps new reasons to express.

Conclusion

To speak with a modern voice while exploring contemporary life and using traditional techniques and tools, is an interesting contradiction. Contemporary painting operates in a similar way. Some may consider oil paint an antiquated medium but it endures because artists find new ways of reinventing the practice every day.

My attitudes about the things Larkin wrote about are much different than his, but his work inspires me nonetheless. Although Larkin’s words embody the voice of post-war England and are very culturally and historically specific, it is also universal. It is deeply concerned with the universality of the human condition.

I have always felt that an awareness of the dire nature of existence is the most life affirming thing to be done. When I remember my own eventual mortality, I am reminded to be better and to live fuller. There is too much to say about a fraction of a Larkin poem but these lines from “Ambulances” seem apt to complete this thought with “And sense the solving emptiness/ that lies just under all we do/ and for a second get it whole/ so permanent and blank and true” (Larkin 104 lines 13-16)

I think about this quote occasionally when I’m driving along an old two lane highway. Like many of Larkins works, this line cuts to the meat of our humanity and lays it bare. Larkin was once quoted “a poem represents the mastering, even if just for a moment, of the pessimism and the melancholy, and enables you-you the poet, and you the reader to go on”. I think that great art is an invitation to wake up. It is challenging and forces us the viewer and the reader to contend with the dormant truths we’ve been suppressing and that remains unresolved or otherwise unexamined. Great art calls forth something that you weren’t expecting to see and you cannot unsee or unread it once you are confronted by it.

Life is finite and within it, there are innumerable constraints. Art as a vehicle for understanding and exploring our infinite universe and finite lives. Art reflects our obsessions with the eternal questions. Although the questions are boundless, the art we make is often defined by limits. There are only so many musical scales to work within. Even non-objective abstract works operate in certain confines such as scale, material, deadlines etc. Material and medium have their bounds as well. A human life is not endless and the human condition is one well defined by limitations. Artists often aim to push these limits and break things, discovering new ways of making and new limits. New definitions and parameters emerge in a continued dialogue about what art can be.

Consider the constraints, use them, curse them and know that they give your work power.

Notes:

Larkin, Philip. Philip Larkin Collected Poems. Edited and with an introduction by Anthony Thwaite.

Sylvester, David, interviewer. "Francis Bacon: Fragments Of A Portrait." TV Documentary, BBC1, 18 September 1966. YouTube, uploaded by Janus Zeewier, 18 April 2013.

"Philip Larkin." Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation, www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/philip-larkin.

Walsh, Stephan. "'What a hole': Hull has embraced Philip Larkin – but did the love go both ways?" The Guardian, 30 May 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/may/30/hull-hole-philip-larkin-poet-love-both-ways

Contact Info