Should Artists Commit to a Style?

Reflecting on the Ka Tokurai retrospective at TFAM: Keeping to My Path

“I only have one life; I only have one destiny. It’s precious.” -Ka Tokurai

I would have never discovered this artist’s work if I had not traveled 7,000 miles from home and stumbled upon his retrospective at the Taipei Museum of Fine Art. Visiting TFAM was a line item on an otherwise long list of things to see while visiting Taipei. And while I oscillate in my belief that life floats atop an undercurrent of destiny vs. a frenetic sequence of happenstances, I think that this happened to be the former. Seeing the work of Ka Tokurai, (Ho Te-Lai, as he’s known in Taiwan), in person did that thing to me which any great show does; it spurred me on to head home immediately and to make art. And so, in spite of having adequate materials in my suitcase to paint, I am sitting at a small table in my hotel room and writing on these ruminations that I’ve been left with after the show.

At some point while wandering through the many halls of TFAM, my wife mentioned that every piece in this show felt like it had been painted by a different artist. The show, titled “Keeping to my path” consists of over 200 works of art that span more than 4 decades. I agreed with my wife’s impression that each work and each room in this show felt vastly different. Works that were hung next to one another didn’t feel like they belonged to the same mind. Many seemed to directly reference other artists and various art movements.

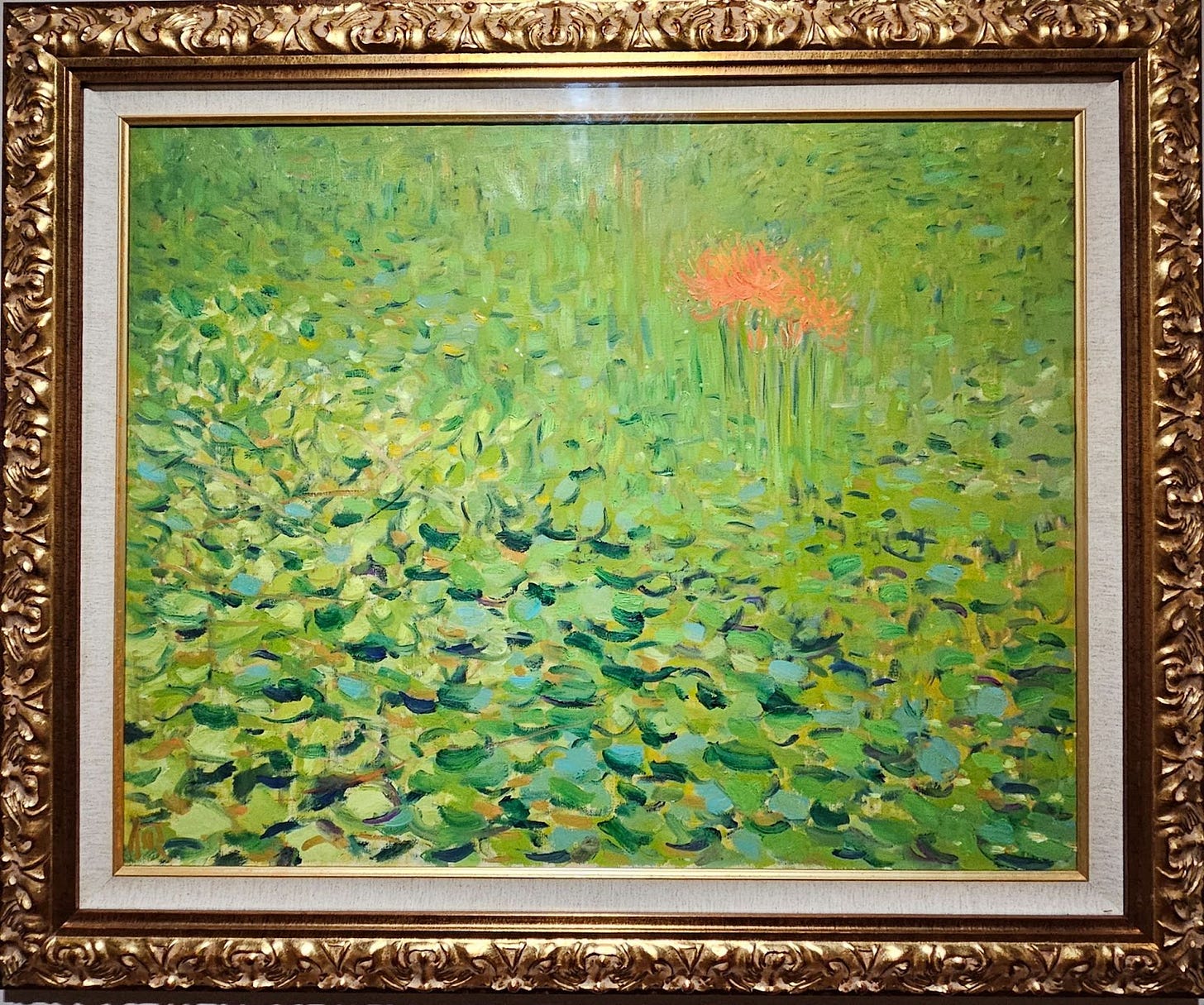

It’s hard to impressionistically paint any manner of lily without drawing comparisons to Monet, but this seems intentionally referential. Other pieces reminded me of the colors and shapes of earlier Matisse paintings as well. Many of the works, for this reason, seemed vaguely familiar.

Some works, however, felt a bit more singular.

Tokurai’s flatter paintings from the 1950’s were among my favorites. The flat surfaces, odd colors and high horizon lines to me felt like nostalgic dreamscapes. After this section, my wife and I agreed that we had wished Tokurai had made more works like the above. Somehow these paintings appealed to our own sensibilities most. Were his style to remain in this place, I would have been happy, as a viewer. I can assume that Tokurai would have been bored to death to remain working in this manner too long. It seemed Tokurai rejected, so vehemently any obstacle to creativity, that he preemptively rejected the possibility of painting himself into a corner.

And so the style of the works continued to change as I walked through the halls of TFAM.

Many of the works used different color schemes, mediums and compositions. There were variations in surface texture, themes, and subject matter. After a time, I expected every room to be the end of the show. But I was wrong on multiple occasions.

It kept on going. Rooms gave way to other rooms and each felt like it could work as a nice punctuation of an already prolific show but there was still more.

The styles of each wing of the museum varied but, upon closer inspection, Tokurai’s mark was evident across mediums and across decades. For example, his lovely calligraphic work filled a couple of large sections of the museum and it was clear that calligraphy was a lifelong practice for him. In many ways these seemed to inform his ink drawings which have a similar lyrical and rhythmic quality and were each likely created with similar tools.

This mark making style exists in his later paintings too. The Brushwork on the mountains of “Mt Fuji in Early Spring”, for example, undulates down in a similar rhythmic way as his ink scrolls and graphite landscapes. This process of articulating the creases in the land with line creates a wispy sense of movement and immediacy which is reminiscent of the direct mark making qualities of calligraphy too.

The show demonstrated Tokurai’s thirst for play and experimentation. There were various iterations of technique that evidence Tokurai’s commitment to furthering his work in all directions. He also explored using his calligraphy in a more literal sense. for example, In “Fifty-Five Songs” and in other works, He employs Japanese characters to form the negative space in the illustration.

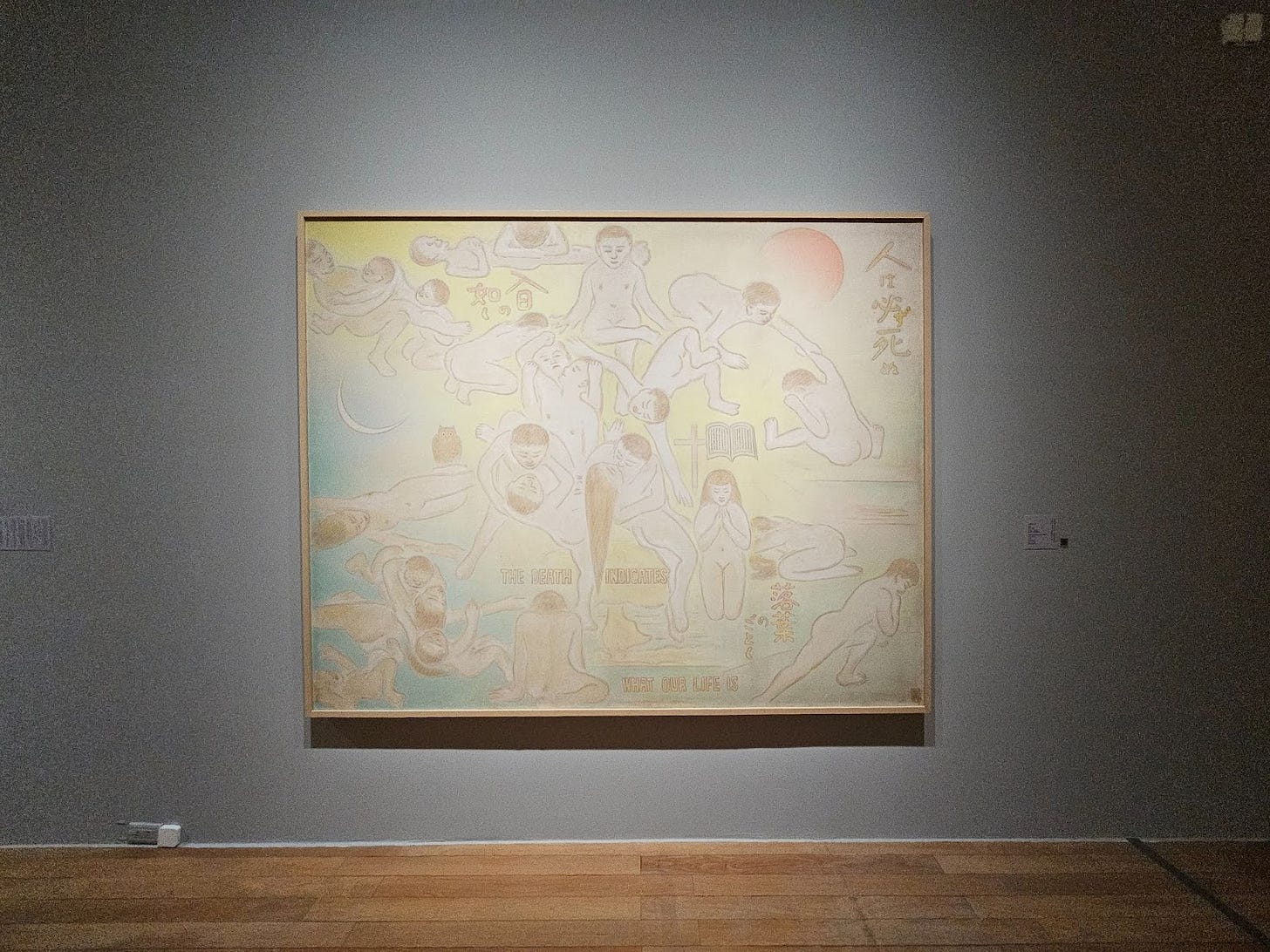

I especially loved this piece.

Its scale was among the largest in the show and the image was flatter and had less value range than other pieces. In this work, Tokurai chooses to literally write the name of the piece in both English and in Japanese and uses the crucifix symbol near the middle of the composition. These choices each seem to break some rule one might have been told in art school; never to use text, cliche or symbols in paintings, but Tokurai would have no time or respect for such a rule/

I just love the innocence, for lack of a better word, in the naivety of the above image, juxtaposed by the nude elements. I am fascinated by the old man who lives in a bustling metropolis, waves to his neighbor occasionally while walking his dog and who quietly paints this piece in his home while nobody is looking. For no one in particular, he makes this unpretentious, unspecific and unflattering look at humanity. This allegorical piece that literally talks at the viewer but does not seem overly didactic somehow.

I am a fan of Sisyphean poses like the one at the bottom right, and I think this is my entry point into this work.

Defining Style

In order to consider why one may dedicate their work to a style, or not, it seems important to at least try to first define what style is.

If I were to define style in art, I would describe it as a collection of marks or manner of making that an artist has refined over time to reflect their unique visual sensibilities (or auditory for musicians etc.). It results from the process of repetitive practice and actively deciding what marks to keep or more fundamentally, what things to keep. Style is a collection of marks or forms of expression which are kept by the artist and which therefore reflect what an artist values. A painter may be drawn to a certain palette for example, or a process which they’ve decided best communicates the central themes in their work.

By this definition, I think that style may arise quite naturally after years of dedicated practice and the issue of committing to a style is already decided upon at this point. The question of committing to a style is secondary to what one does by manner of habit anyways in most cases.

Still, this doesn’t portend that one must stay within these parameters forever and certainly styles can evolve and be consciously reimagined by an artist.

Across one’s life, there is always also the indelible mark which no artist can escape and it’s their own hand. Honing style, I think it is finding these things which make one unique and that are often mistaken for failure. If El Greco was frustrated by his mannerist way of depicting the human form paired with his sickly and unnatural color pallets, the world is still better off for having these imperfect masterpieces.

Tokurai is a great example of one who worked in unwavering service to his own vision. Even if that vision changed frequently. His work may reflect an anti-style but still evidences his commitment to exploring art from every angle that he fancied. He wasn’t concerned with selling works and so, he had no clients, gallerists, dealers or even critics to please.

This afforded him the complete license that artists often forget that they have and that is to make whatever they want.

Email: info@zachkmendoza.com

Thanks for reading Painter's Paint! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Thanks for turning me on to Tokurai and your commentary is interesting and helpful.