Why You Should Take Nonsense Seriously

Considering Dada and the writings of Tristin Tzara

“The absurd doesn’t frighten me because, from a more elevated point of view, I consider everything in life to be absurd”

-Tristin Tzara

The gentle breeze of Spring carries a yellow wall of gas across the fields of Warsaw. Scouts report the encroaching miasma to their superiors. The men are ordered to hold their positions but the generals have no idea what is approaching. We know now that the toxic Chlorine gas is heavier than air. As it settles in the trenches, thousands of unsuspecting soldiers begin dying excruciatingly from asphyxiation. Lungs and other soft tissue melt inside uniforms like tubs of ice cream left out in the summer. The surviving men who can walk retreat to the neighboring town. Doctors there are ill-equipped to treat the wounded as they’ve never encountered such a weapon. The soldiers who remained unblinded were sent back to the front lines immediately.

In 1915 the world experienced innumerable horrors. The First World War saw the advent of machine guns, tanks, and chemical warfare. Mankind had unleashed the most novel and horrific methods for human destruction that the world had ever seen. Thousands routinely fell defending holes in the ground or conquered yards of territory only to have these yards conceded the following month. This capricious mass casualty cycle would repeat for the next few years resulting in the demise of millions of people. The incredible loss of life was in a word, absurd.

In an upended world, it is no coincidence that 1915 was also the year that birthed a new literary, artistic, and philosophical movement called Dada. During the war, artists and writers throughout Europe fled to neutral Switzerland. German and Romanian Pacifist writers, poets, playwrights, and painters were among the artists of this migration. Their union coalesced around a rebuke of the horrors and darkness of the time and their movement was called Dada. Dada was anti-everything. It was anti-war, anti-bourgeois, anti-materialism, anti-establishment, anti-museum, and even anti-reason. Dadaists saw the world now subject to the whims of the international war machine and Dada was formed in absolute protest. The mechanisms that precipitated this cataclysmic period seemed arbitrary and Dada was both a reaction to and an embrace of the arbitrary.

Proponents of Dada protested intellectualizing art in the same way it protested how we intellectualized and rationalized wars. It detested the ruling class and the powers behind the levers of war and industry. Dada art manifested into an unadulterated embrace of the nonsensical. Centuries of technical rigor were discarded in favor of found objects flippantly mounted on pedestals or hung on white walls to mock the conventions of the art that took itself so seriously. Ad hoc piano and dance performances at the Cabaret Voltaire saw musicians improvise whole songs out of tune while others danced. Ready-made objects became a preferred method of construction for sculptors of this time.

A few years before Dada’s emergence, Marcel Duchamp painted the modernist masterpiece “Nude Descending a Staircase”.

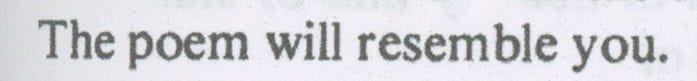

This painting blurred the lines of the cubist and futurist movements while forwarding the conversation about modern painting. This work evidenced the brilliance of Duchamp the painter and was the first piece that solidified his prominence as an artist. It must have been shocking to a follower of Duchamp’s work to see his great “Fountain” work then five years later:

It was a urinal, not fabricated by the artist but rather “found” somewhere and signed. Duchamp famously signed “R.Mutt” on this urinal and the rest is (art) history. Duchamp was a revolutionary artist who was concerned with reframing our definition of art. He was interested more in the conceptual considerations of a piece than the visual techniques and this sculpture perfectly encapsulates Dada’s irreverance.

“Fountain”, and the Dada movement as a whole was a revolution in art. Just like other forms of revolution, it required bloodshed. Dada sought to slaughter convention. Its members would reject the history and traditions of high art as well, in favor of art that was subversive and that violently shat on everything that came before it. It was a movement that sought to throw the baby out with the bathwater and then proceed to burn down the entire bathroom and dance around its ashes.

Many of the great art movements of yore were formed as a rejection of previous movements and Dada was perhaps the most radical example. One of the lessons I’ve learned from Dada is that, on an individual level, this disruptive ethos can be applied to one’s own art practice. When a painter feels like their work is becoming stale or predictable introducing some unexpected marks can reframe one’s practice. If you feel stuck in your work, introducing some unpredictable chaos is not the worst idea and it may even be necessary for progress. Tear things up and reassemble them. Find sticks and dip them in ink so that you can scratch them across long surfaces. Find a library book and open it to random pages while taking a word here and there for direction. All of these are powerful methods for creation - taking some cues from the arbitrary.

Personally, I’ve never been much moved by the images of DADA, but the ideas at the center of the movement are inspiring. The artist's spirit of re-invention and spontaneity is worth cultivating.

“What we want now is spontaneity. Not because it is more beautiful or better than anything else. But because everything that comes from us freely without any intervention from speculative ideas, represents us.”

-Tristin Tzara

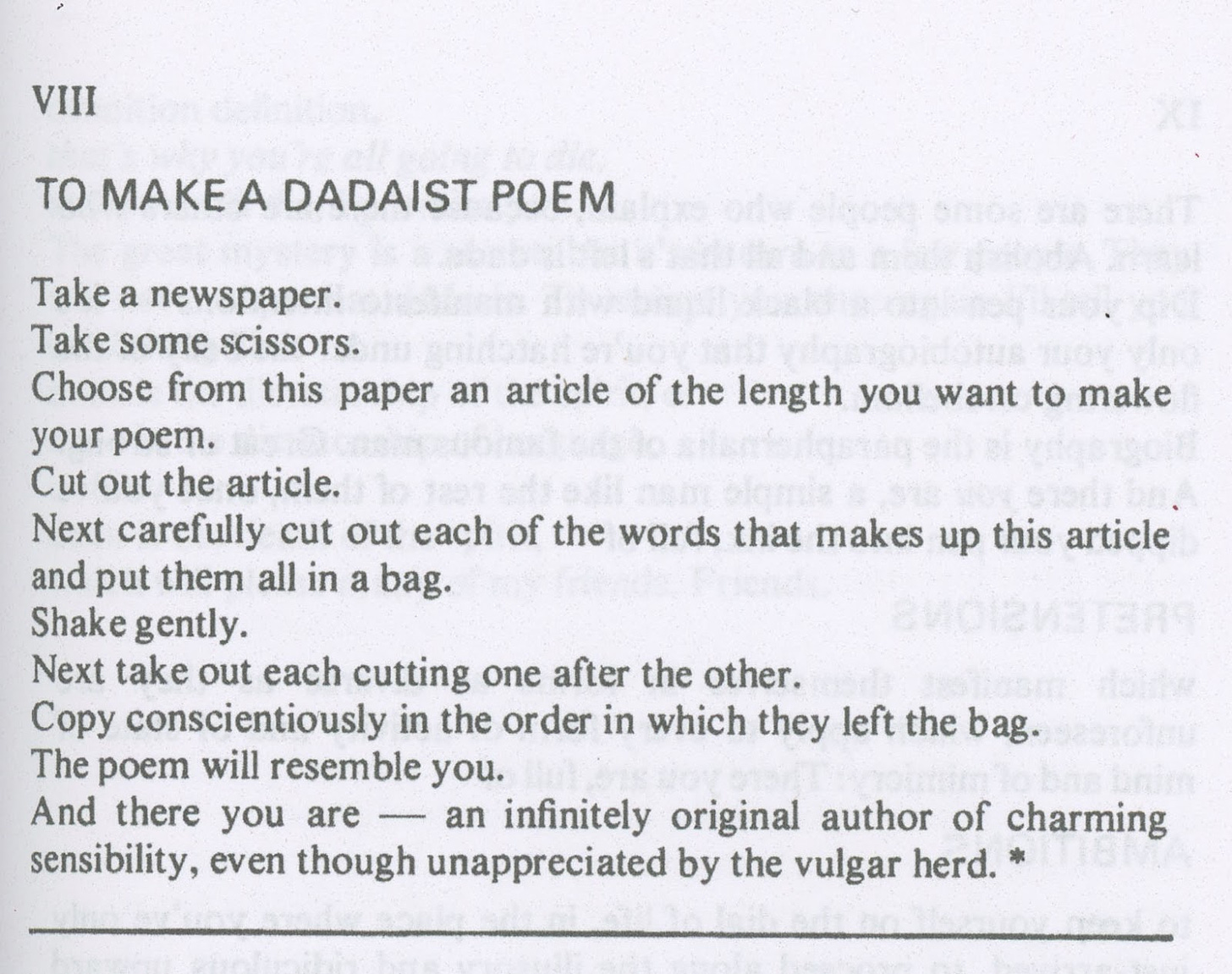

The best exponent of Dada's ideas is Romanian writer Tristan Tzara. Tzara wrote the Dada Manifesto which he used to outline many key points in the philosophy of Dada. In his Seven Dada Manifestos, Tzara provides a detailed treatise of what Dada is in a series of short essays and Lampisteries, as he calls them. Perhaps the most well-known among these is Tzara’s “How to Write a Dada Poem”

Such a process operates entirely outside of reason. We are asked to construct a series of words randomly selected from magazine clippings and then arrange them into a poem. Tzara suggests that this assemblage of letters will make our writing “infinitely original”. The random compiling of word clippings is like a crypto seedphrase which is impossible to crack or to replicate through logical processes. The “herd” in Tzara’s poem seems to be the established order, gatekeepers, and the artists who follow their prescriptions for what art should be. But in this poem, one line always stands out to me:

How does a poem constructed entirely of arbitrary processes resemble you? Well, Tzara would likely assert that you were also made of arbitrary processes and that existence confounds logic and encourages a healthy relationship with the nonsensical and a recognition of the impossibility of life. Art should echo life and vice versa. A poem configured by wholly spontaneous action reflects you in this moment. A dadaist aims to act with the materials before them without an intermediary (even if the intermediary is their logical mind). Artists, in this sense, are stenographers transcribing the experience of making something. In a painting, the smattering of pigments on a surface preserves the painter’s action when they create it. If we can cultivate more of these moments in our work, we might just surprise ourselves.

We can use the lessons of Dada to interrupt what we are doing or to subvert our own expectations, in the same way that Dadaists sought to surprise their viewers 100 years ago. The act of disruption is a useful one because often artists can plateau into a comfort zone and produce work that is no longer challenging.

Precursor for Surrealism

Tzara’s writings and Dada more broadly would become a precursor for Surrealism.

"To become truly immortal a work of art must escape all human limits: logic and common sense will only interfere. But once these barriers are broken it will enter the regions of childhood vision and dream."

―Giorgio De Chirico

Surrealists continued to look for ways of circumventing the prefrontal cortex to make work that transcended expectation and rationale. Some, such as Dali, experimented with sleep deprivation to find new ways of seeing in their work.

Artists like Dali and De Chirico explored new methods of transcribing the subconscious to create a pictorial plane that reflected the dream dimension. De Chirico says an immortal work escapes human limits. Many surrealist painters also reintroduced a refined painting technique in their practice which involved highly rendered and modeled surfaces mixed with experimental scale, texture and imagery. Dali, Max Ernst, Dorothea Tannig and others would employ impressive rendering techniques, echoing those of the old masters but motivated by surrealist and dadaist conceptual considerations.

Contemporary Example

Among contemporary painters, Adrian Ghenie is one who has cited Dada as an influence and he uses it as a point of reference in several of his works.

In this piece, Ghenie directly references a photo of the first international Dada fair that took place in 1920. Ghenie is well known for anchoring his work to moments and figures in history and art history and exploring the conflicting ideologies of the 20th century. He is also recognized for the bold and expressive manner that he paints, which I’ve heard him explain arrives out of necessity. Experimentation, as he sees it, is essential to keep the painting fresh and to not lull oneself into a state of boredom and automation.

Conclusion

Understanding the historical context in which Dada emerged, makes it easier to see why artists of the movement were so daring in wanting to destroy all of the structures and convention that came before. Sometimes it takes a tragic rift in the fabric of existence to see our world differently. Values and ideas may experience a seismic shift revealing some glorious unknown.

Articulating why random processes and experimentation is essential to forward one’s practice and make sense of it all seems nonsensical, and that’s the very reason why it should be taken seriously. Overcoming the fear of messing up, the fear of deviating from a vision, the fear of the unknown will give way to something better, something fresh.

When someone responds to an ink blot, spill an accident that you liked and kept, they are responding to the immediacy of you in your work. The humanity and the wabi-sabi. If you feel stuck or painted into a corner in which you make good looking work that is stiff and without risk, I implore you to introduce a bit of the random. Start off with a vague idea and allow room for spontaneity. Allow yourself to wander into a dark forest and slash your way out of the thick brush with a pocket knife. This is the best way to unearth something and to make discoveries.

“I’ve never started a poem yet whose end I knew”

-Robert Frost

A work determined from the beginning has no way of surprising you, the artist, and you the viewer. Paintings have a way of dictating where they need to go and what they need to become. I’ve found that when I listen to this dictation, I discover things I couldn’t have planned for. Season the stew of your work with the dust of the absurd and, much like a Dada poem, it will resemble you.

Notes:

Tzara, Tristin. Seven Dada Manifestos. Translated by Barbara Wright. 1924

Manufacturing Intellect. (2018, January 24). Dada and surrealism: Europe after the rain documentary [Video]. YouTube.

National Army Museum. (n.d.). 1915: Early trench battles. National Army Museum. Retrieved [October 21, 2024], from https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/1915-early-trench-battles

Contact Info